Stacie Sheldon on courage, language, and identity

From learning her heritage language to infusing UX with empathy, senior consultant Stacie Sheldon brings a powerful listening ear to Slalom Detroit.

Chitwaadewegekwe knows the power of storytelling.

Or Stacie Sheldon, as many people know her.

“Knowing your name means knowing your place in the universe,” Stacie says to a virtual audience in a presentation on Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Her Ojibwe name—Chitwaadewegekwe—means “Honor Beat,” representing the accent beats that come between the regular drumbeats in many traditional American Indian songs.

“The drum is really important to Anishinaabe people because it’s a representation of the heartbeat of the people,” she says. “I think I was named Honor Beat Woman because of how much I enjoy those strikes in the songs.”

Anishinaabemowin is the language spoken by the Ojibwe (also known as Chippewa), Odawa, and Potawatomi communities throughout both the United States and Canada. It’s part of the Central Algonquian language family—a group of related Indigenous languages spoken throughout Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan, and beyond.

Originating from Cheboygan, Michigan and a member of the Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians, Stacie didn’t grow up speaking her heritage language. Due to federal policies of assimilation—including boarding schools—most Native American languages were suppressed and have become endangered. In 1990, the US passed the Native American Languages Act, allowing for the preservation and protection of Indigenous languages.

It wasn’t until 2006 at a community language table that Stacie began learning Anishinaabemowin.

“You weren’t doing a favor for your children if you spoke your language to them,” she says. “So most people my age and younger didn’t grow up speaking the language.”

That same year, Stacie co-founded Ojibwe.net—a website that serves as a resource for those who want to learn Anishinaabemowin.

“As with a lot of creative endeavors, we didn’t start off with a plan,” she says. She and co-founder Margaret Noodin recognized that there weren’t a lot of written materials in Anishinaabemowin, so they began collecting documents and inputting them in a server, gradually transforming the website into the library of knowledge that it is today.

This ability to serve as a resource for her community is something she brings not only to her advocacy efforts but to her work as well. According to Jonathon Baugh, director of experience design at Slalom Detroit, it’s her exceptional ability to support and teach some of the more junior team members that makes her stand out.

“With Stacie, it’s sponsorship, not just mentorship,” says Jonathon. "She really is building and shaping a better future. That’s what it boils down to.”

From curating a repository of research to constantly giving her teammates the spotlight, Stacie always goes above and beyond what’s asked of her.

“When I’m hoping for sticky notes, Stacie shows up with a spreadsheet,” says Joshua Ribolla, Stacie’s people leader.

He shares a recent experience in which Stacie was being interviewed by Michigan Public Radio about her language advocacy work. Knowing she had a few team members who wanted to expand their presentation skills, Stacie asked the interviewer if she’d be willing to come speak with her Slalom team on the topic. The interviewer said yes.

“It was classic Stacie,” Joshua says. “She had a teammate she wanted to help, so she was willing to go outside of her comfort zone. I’m not sure she would’ve done it if it would’ve been for herself.”

All of these efforts are connected to two of Stacie’s core values: courage and authenticity.

And courage is an attribute few people embody as boldly as Stacie does. She’s opened her life up to her team in a lot of different ways, Joshua says, reflecting on her Q1 presentation as an example.

“Our state bird in Michigan is the American robin,” Stacie says to the virtual audience. “But I think the chickadee should be our state bird. It stays with us all winter, and it never leaves. It reminds us of those who have survived.”

She then sings an excerpt from the book Gijigijigaaneshiinh Gikendaan (What the Chickadee Knows) by Margaret Noodin—a collection of poems written in both Anishinaabemowin and English.

“As the song says, the chickadee—the gijigijigaaneshiinh—calls to remind us to celebrate how we live,” she says.

“She’s just so magically human,” says Gina Herakovic, a teammate of Stacie’s on the experience team. “She brings her whole self to work, and she’s not afraid to talk to people about it.”

When I ask Stacie about the bravest thing she’s ever done, she pauses.

“I’m going to write that down,” she says. “Can I get back to you?”

Her ability to make space for reflection comes through in her response to every question. It reminds me of something she shared in her presentation: the Anishinaabemowin words for peace and listening are similar. To listen is peace.

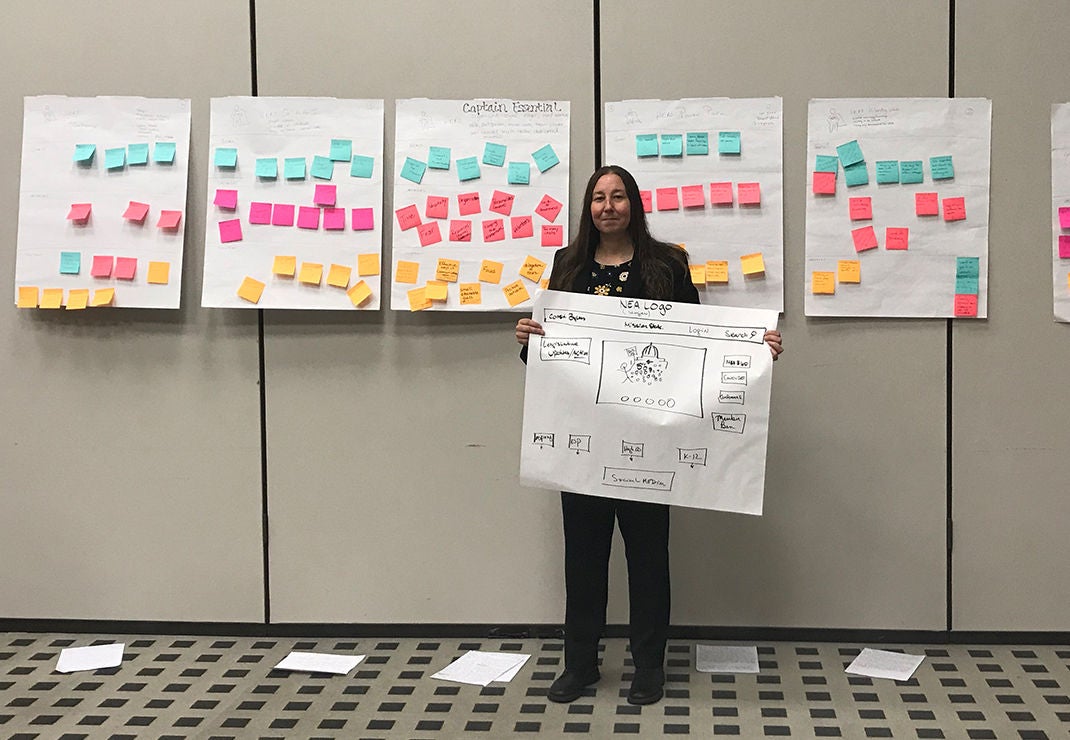

“With user research and design, being able to observe and listen is the vehicle of any success that I have,” she says. “I want to understand people’s perspectives, where they come from, who they are.”

It’s not only a passion of Stacie’s but a talent that’s recognized by her team at Slalom.

“She has the ability to create safe spaces for people, and I think that’s rare,” says Gina. “She really sees you.”

A big part of this, Stacie mentions, comes from often feeling like an outsider looking in.

“I’ve always felt on the border of things,” she says. “It’s benefited me as a researcher and designer because I bring that mindset to my projects and my work. I can listen to what someone is saying and figure out a way to help them based on what I’m actually hearing.”

But this level of mindful listening requires a vast amount of empathy—something that has been a driving force for Stacie as a senior consultant at Slalom Detroit.

“I think the discipline itself is designed to be empathetic—to teach us about others and how to feel for others,” she says. “What I think needs work is how organizations adopt and operationalize UX design and research practices.”

While Stacie’s accomplishments seem vast and impactful, she doesn’t necessarily see it that way.

“I don’t know that I’ve thought of myself in terms of achievements,” she says. “I like thinking of myself as a maker of things.”

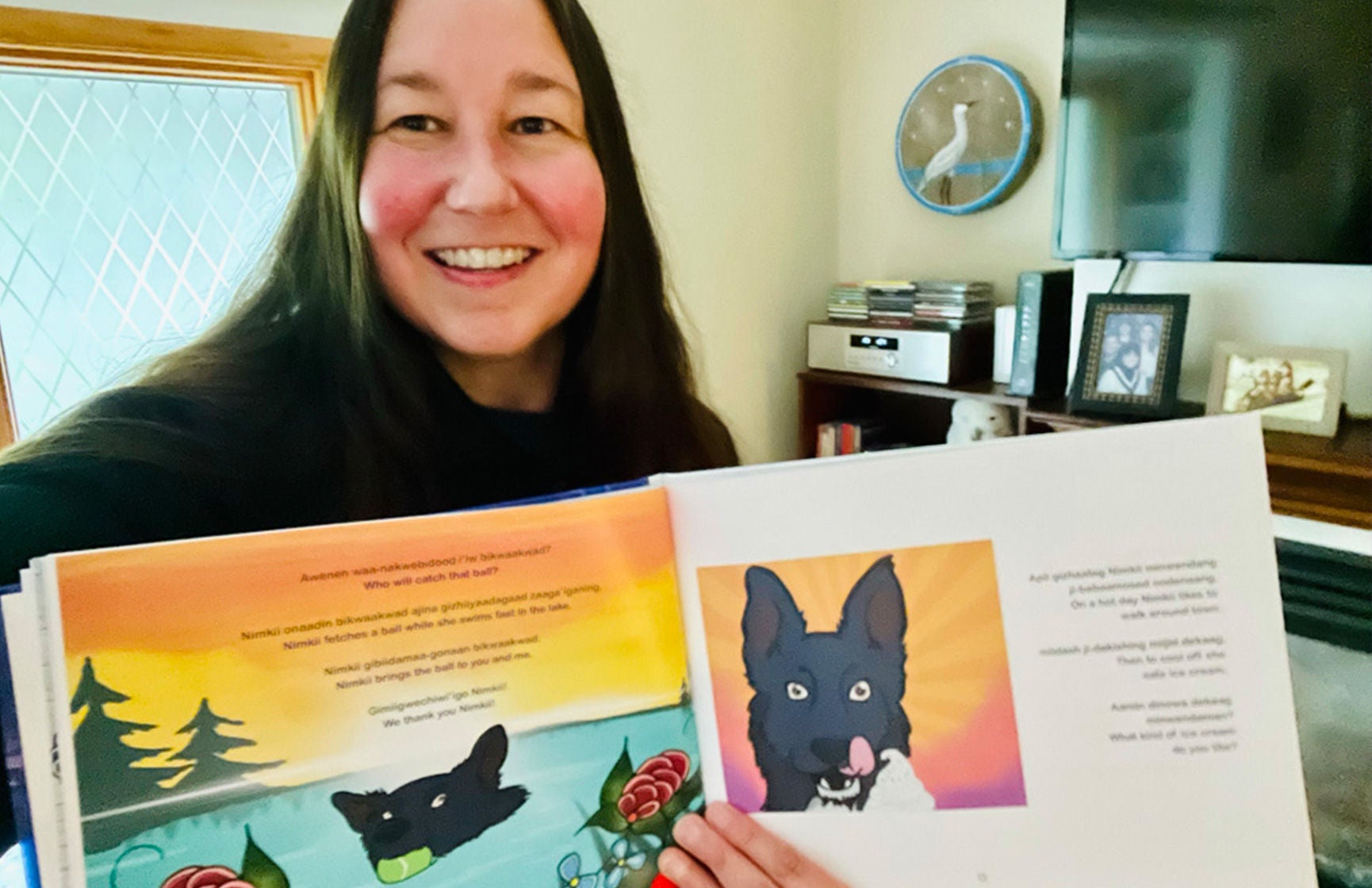

This includes writing and publishing her first children’s book—Bebikaan-Ezhiwebiziwinan Nimkii: The Adventures of Nimkii. When asked about the inspiration behind the book, Stacie says with a laugh, “I just happened to have a super cool dog.” While there are many books in Native culture that focus on history or traditions, she saw the need for an American Indian book that focused on life today.

“While all of those things are important, I wanted to show that we’re a modern people as well,” she says.

For Stacie, her identity is an amalgamation of many things: UX expert, advocate, author, musician, sister, friend.

While this mix of identities has proved to be monumental in her career and given her a great capacity for empathy, it’s something Stacie has only become comfortable with over time.

“In all my years in tech, I’ve never met another American Indian,” she says. “I’ve never had an American Indian co-worker. I’ve never had an American Indian manager. I’ve always felt pretty alone in that regard.”

Between a rise in social justice discussions to being recruited at Slalom, Stacie says she’s slowly been able to embrace all parts of her identity.

“I like seeing that Slalom walks the walk on its commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusiveness,” she says. “I’m definitely able to be my whole self at work in a way now that I never have been in the past.”

That said, there are still many changes that can be made at the state and congressional levels—as well as within our direct communities—starting with visibility.

“There are 12 federally recognized tribes in the state of Michigan and 140 sovereign nations in and around the Great Lakes watershed,” she says. “I would like the people of Michigan to know we’re here.”

Stacie hopes that spreading awareness could also lead to Ojibwe language classes being offered at schools across Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota as part of a Native language department. While some schools such as the University of Michigan and Michigan State offer Ojibwe classes, she says, the fluent elders leading the classes aren’t traditional academics.

“You can’t just hire a teacher—you need a partnership,” Stacie says. “So I’d love to see them get the support they need in and out of the classroom to facilitate that.”

A few days after our conversation, Stacie follows up with me.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about your question about bravery,” she says. Instead of one big moment, she shared a series of small ones. Singing at a recital. Calling her adoptive father “Dad” for the first time. A difficult breakup. Playing her first gig. Walking across Lake Superior in the winter to see the ice formations on Grand Island.

She says her favorite teaching on bravery is having the mental and moral strength to overcome fears that prevent you from living your true spirit with the same vigor and intensity with which a mother bear protects her cub.

With these reflections, identities take shape. Mother bear. Chitwaadewegekwe. Heartbeat of the community.