Unlocking M&A deal value in commercial life sciences organizations

In what has otherwise been a challenging market for mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in the past year, the life sciences industry has proved to be comparatively resilient and active, particularly for corporate and strategic acquisitions. Given the more challenging economic and deal financing conditions at the moment, the willingness to be more speculative in the actual delivery of value capture has eroded, affecting how executive and corporate development teams need to think about planning and executing integration.

As we look at the common types of deals in the life sciences industry, we’re examining the integration strategies and challenges that enable and inhibit the extraction of deal value. Across the different deal types, the common theme is to deeply understand the deal thesis — why you are doing the deal in the first place — and to relentlessly focus and anchor integration activities to center on those points of deal value.

The challenges found in life sciences integrations are uniquely complex to the industry, and the types of deals are much more varied in their structure and purpose than in other industries. Understanding the acquisition categories and how they influence the deal thesis is critical to developing an integration plan that delivers the intended value.

The focus of this article is to walk through the common transaction types and to spotlight key integration challenges and solutions for the combination of two larger, commercialized, mature life sciences organizations.

Common deal types in life sciences

When examining the deal theses across acquisitions in the industry, the rationale and purpose for pursuing the combination generally fall into one (or sometimes more) of the following categories:

- Pipeline building

- Portfolio realignment

- Market access

- Commercialized or mature acquisitions

One important note is that for the purposes of this article, we are looking at instances of acquiring or divesting majority control of a company. The range of deals in life sciences goes well beyond this when taking into consideration in-/out-licensing, venture investment, or other operational and commercial distribution agreements, among other forms.

Pipeline-building

These deals are generally acquisitions of pre-commercial companies or carved-out research and development (R&D) assets that the acquirer believes they can successfully commercialize and bring to market more efficiently via their more mature launch and go-to-market capabilities. Examples include Lilly’s acquisition of DICE Therapeutics and Novartis’s acquisition of Chinook Therapeutics. Pipeline deals often have earn-out or milestone-based structures as part of the purchase price.

Portfolio realignment

These deals can take many forms, but in current economic conditions (and in similar prior circumstances), these will include divesting noncore assets, bundling similar assets from multiple companies into joint ventures, or consolidating operations in the form of internal restructurings to better realize value out of those businesses. Recent examples include Viatris’s series of divestitures to focus on their core therapeutic areas or Baxter’s spin of Vantive.

Market access

These are a specific type of acquisition that helps enable regulatory approval and subsequent product launch in a specific geography, sometimes due to local regulatory requirements for business operations or because of existing approvals already held locally by the acquired company that the acquirer can then build on.

For this article, we’re focusing on the final type: commercialized or mature acquisitions.

Combining two mature life sciences companies

These types of deals are characterized by the combination of two mature companies with commercialized products, sales teams, supply chains, regulatory environments, and robust support organizations, with specific revenue and value-capture targets attached. Broadly speaking, synergies may be delivered through efficiencies of scale, enhanced revenue opportunities, and otherwise streamlining operations as a combined organization.

We will highlight a few key complexities with this type of deal and how best to address them, but the starting point for an integration leader and an integration management office (IMO) should always be to clearly define the deal thesis. This summary of the deal rationale will be the ultimate test of success in an integration and will frame the entire approach. An integration team should begin with a handful of questions:

- What are the core reasons we are acquiring this company instead of pursuing another route?

- What does this company deliver that we could not do ourselves?

- Where are the specific areas of synergy identified in the deal process, and on what timeline are they expected to be achieved?

- What assumptions and decisions are part of the deal process?

Answering these questions will go a long way in defining the deal thesis, and doing so at the outset will allow the teams to build integration and synergy plans that deliver on the deal rationale. Assigning owners as single points of accountability and defining objective success measures are the next steps that will frame the integration team and plan.

For example, if reassessing commercial footprint (e.g., moving from distributor model to direct local presence) or reconfiguring the operating model (e.g., combining supply flows, entity structures, and accounting for regulatory impacts) as a combined company is part of the deal thesis, setting up dedicated cross-functional integration teams with clear points of accountability early in the process will be critical. Having those teams then build out cross-functional plans tied to the deal thesis, complete with specific synergy goals and owners, will be essential to realizing the envisioned deal value.

Complexities of integrating commercialized or mature companies

While there are common activities across all industries when starting an integration (e.g., setting up the IMO, onboarding employees, managing synergies), for the purposes of this conversation, we’d like to highlight some of the more unique aspects of deals and possible focus areas for this type of acquisition in the life sciences industry.

Regulatory environments and longer sign-to-close period

In the past few years, the FTC and DOJ have heightened scrutiny of life sciences mergers due to concerns about drug pricing and overall competition. The implications are longer and more uncertain paths to close.

Consent orders may be issued following lengthy regulatory reviews and discussions and might only be issued after a satisfactory removal of the anticompetitive concerns. Example resolutions might include divestitures (e.g., Otezla divestiture to Amgen to gain approval for the BMS — Celgene merger) or other restrictions on certain products/therapeutic areas of the combined portfolio (e.g., restrictions on Tepezza/Krystexxa for Amgen — Horizon merger). Having to account for these types of changes in the deal affects timing, avenues to value capture, and, in some cases, the deal thesis itself.

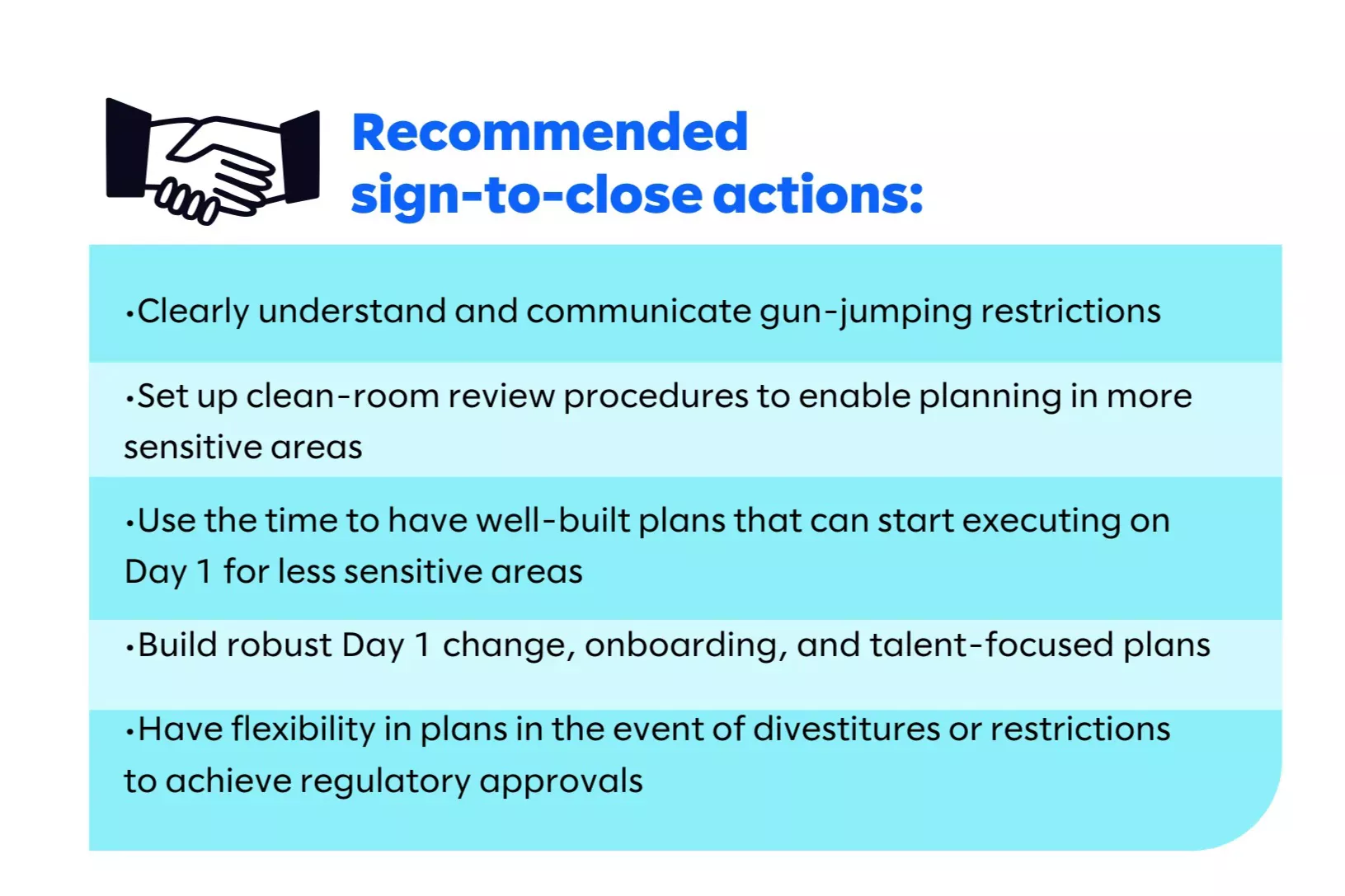

IMOs have to adapt to the longer sign-to-close period, designing programs that take advantage of the extra planning time while ensuring compliance with pre-close gun-jumping restrictions. If an IMO appropriately utilizes the pre-close timeline, more complex integration activities can kick off execution on or close to Day 1, accelerating completion post-close. IMOs that have not effectively used the sign-to-close period may face a complex integration and a more challenging people/change environment in the combined company due to uncertainty and frustration in the process.

Operating model integration

Commercial and globally positioned life sciences companies operate in extremely challenging, complex, and highly critical circumstances, even on a standard day of business. Combining two of those models is an incredibly challenging effort and should not be underestimated.

When discussing an operating model in this context, we are referencing the set of physical flows and financial transactions that need to occur to make the business run. When do products ship, from where, and when do they legally enter a country? Where does product finishing occur? What invoices are sent and when? What legal entities are involved? What third-party relationships exist? These are just a small handful of the questions that need to be answered to document the model, and harmonizing two different companies into one cohesive model that covers all geographies takes a well-thought-out cross-functional effort.

The combination of the global operating model drives the pace of the overall integration and is a significant determinant in timing to achieve cost synergies. Highly complex and cross-functional in their own rights, legal entity consolidation, supply/logistics integration, and systems consolidations are all necessary to deliver on the end-state model.

To give an example of what goes into just one part of an operating model workstream, legal entity consolidation includes activities like employee transfer, marketing authorization transfer, licensing changes, customs/import changes, label changes, system consolidations, and other regulatory/quality activities, without considering the other local regulatory, commercial, brand, supply, and systems changes that might need to be taken into account.

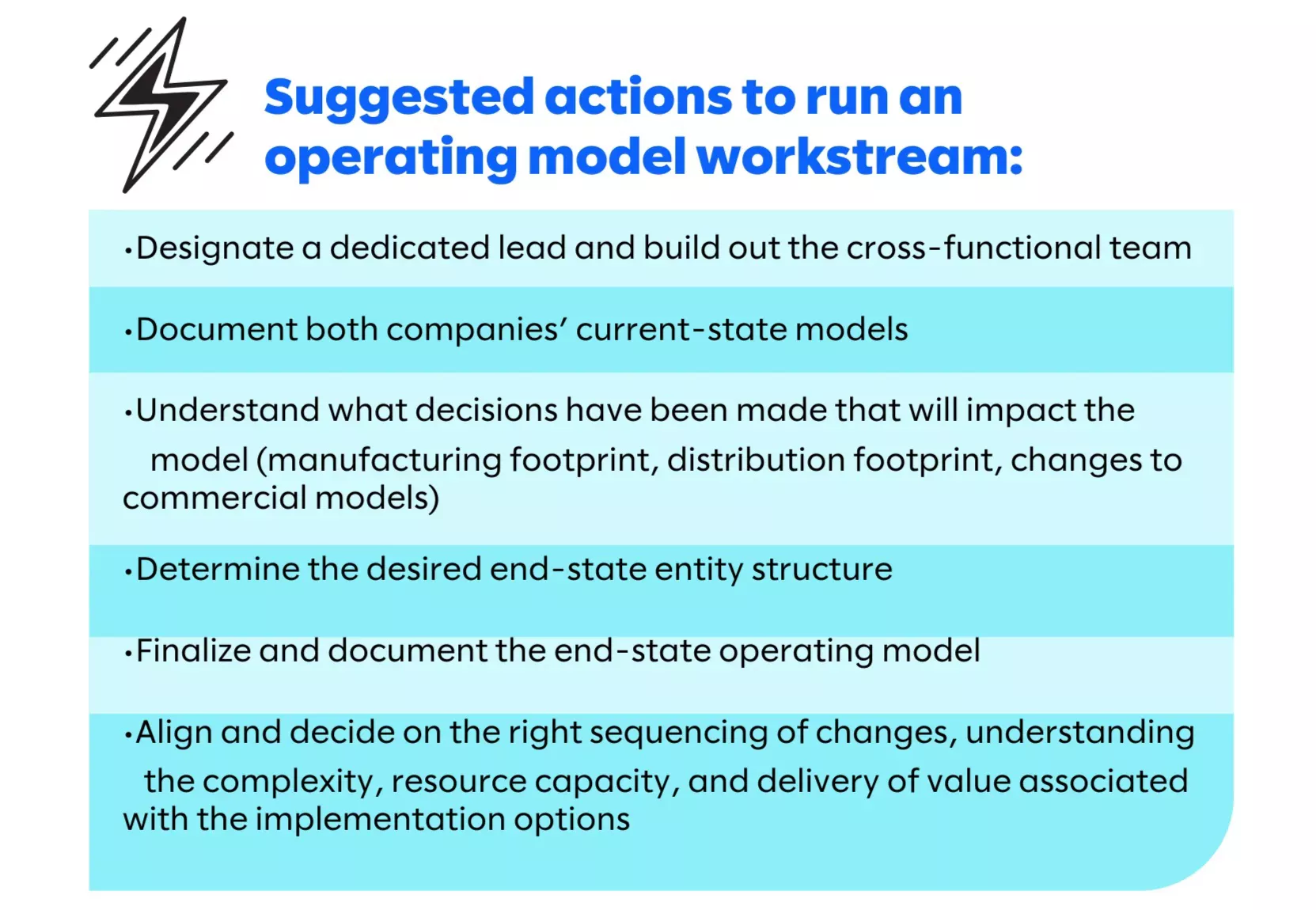

Successfully managing an operating model integration requires direct coordination of the cross-functional effort, with clear ownership as part of the IMO, effective decision-making bodies to help drive the work forward, and cross-functional representation within the workstream.

Determining the future-state footprint

A critical driver of revenue and cost synergies is defining the combined company’s commercial, manufacturing, and distribution footprints. Doing so is a significant input into the prior discussion on the operating model, as that workstream must know what they are building toward to set up the right support structures.

For commercial footprint, an important starting point is determining what commercial model should be in place on a market-by-market basis as a combined company. Do the combined scale and local market dynamics / growth opportunities warrant moving both companies from a local distributor model to having a direct local presence? For markets where one has a local presence and the other does not, does it make sense to pull products into the direct local model, or do the market conditions (e.g., new regulatory restrictions) warrant both downshifting into a distribution model? Finding the right mix on a market-by-market basis can drive many of the commercial synergies, whether through exiting distributor contracts or introducing new products to the market and sales force.

Similarly, for the manufacturing footprint, combining sites can be a significant driver of cost synergies, but doing so is often the longest pole in the tent in life sciences integration. Complexities in managing regulations and environmental, health, and safety (EHS) requirements, completing tech transfers, fulfilling third-party-manufacturing obligations, managing employee relations, and effectively replacing supply elsewhere are all part of the difficulties in optimizing the manufacturing footprint. Understanding the respective site capacities, capabilities, performance, and reliability, as well as how each site fits into the overall network and systems, is critical to deciding what the future-state footprint should look like. Some markets may also require local manufacturing or local labs (e.g., Indonesia and Brazil), which also needs to be considered.

On the distribution footprint, a similar process to understand what capabilities are needed across the network for the combined portfolio will be essential. For example, if cold or ultra-cold storage is required through the distribution process, having that chain retained and in place will drive where other consolidation will be possible. Aligning on products that require unique or dedicated logistics models will also be part of this process. For example, cell therapy solutions have a vastly different logistics flow than pills or capsules in bottles. Also, understanding the desire to minimize supply points or otherwise consolidate into regional distribution centers will be a major driver of complexity, depending on the current state of both companies. Like the manufacturing footprint, many markets also require local warehousing, which will need to be accounted for in determining the overall footprint.

Each of these footprint conversations requires dedicated teams, clear ownership, and a significant amount of time and information to finalize. The added complexity is that these areas are sensitive, meaning information may not be directly available until after closing. Using pre-close clean room structures can accelerate insights, however. Getting these decisions right and quickly moving forward will be key to delivering deal value.

Harmonizing R&D

Integrating R&D functions in an acquisition is a challenging and intricate process, as it involves combining scientific talent, research programs, technologies, and infrastructures. Successful integration can lead to enhanced R&D capabilities and portfolio expansion, but if mishandled, it can result in loss of key talent, project delays, and even the termination of promising research programs.

Tying back to the deal thesis and prioritizing R&D programs based on the strategic goals of the combined entity is a critical part of successful integration. The first major step is conducting a thorough assessment of both companies’ R&D pipelines and, based on those aligned strategic goals, deciding on the continuation, reprioritization, or discontinuation of specific programs to minimize redundant efforts and allocate resources efficiently. Also, review ongoing collaborations, licensing deals, and partnerships and decide on continuing or restructuring these relationships based on the combined company’s strategic direction. Synergies can be defined as part of this process, as well as aligning on budgets for ongoing and future R&D projects and addressing financial commitments related to milestone payments, partnerships, or licensing deals.

Identifying key R&D personnel crucial to ongoing and future projects is critical to maintaining pipeline momentum and success. If there are highly regarded researchers and principal investigators in the organization, offer competitive retention packages, clarify roles post-integration, and pull them into defining the vision for the future R&D organization to minimize departures. Another key step in pulling the respective teams closer is to facilitate knowledge-sharing sessions and training programs to ensure a uniform understanding of technologies, platforms, and therapeutic areas.

Also critical in the harmonization process is understanding the regulatory status of ongoing programs and maintaining the integrity and quality of clinical trials and other R&D projects during the transition. The IMO workstream leads should provide clarity on R&D operations, how reviews will be conducted, setting up combined advisory boards and review panels, and how internal and external stakeholders, including staff, partners, academic collaborators, and regulatory agencies, will be engaged.

Depending on the overall integration strategy, consolidating R&D facilities, labs, and equipment might be part of the plan, as will harmonizing processes, protocols, and standard operating procedures. Doing so while ensuring systems compatibility, especially in data management, IT infrastructure, and lab equipment, is critical. Conducting thorough intellectual property (IP) due diligence to identify patents, licenses, and other rights, addressing potential overlaps or conflicts, and ensuring the seamless transition of IP should all be part of the integration plan as well.

Rising above the complexities

These preceding areas are only glimpses into the level of underlying complexity present in the integration of two mature, commercialized life sciences organizations and are incremental to the many already-complicated integration workstreams that exist in other industries (e.g., systems integration, people integration, change management). To sort through the complexity, the IMO should always anchor back on the strategic rationale and deal thesis for the acquisition. In so doing, building recommendations and going through the decision-making process can become less challenging.

While the deals discussed here are the most complex and time-consuming across an entire organization, the other deal formats have extremely important nuances, where attention to detail and addressing those issues early in the process will be critical to success.